Do you suffer from tree blindness?

You may be entitled to compensation! (Just kidding)

For this assignment, Dr. Klips introduced us to a New York Times article titled “Cure Yourself of Tree Blindness” by Gabriel Popkin. The author describes tree blindness as a total lack of knowledge of the trees in your daily life. But they also write that not only is tree blindness easy to cure, but it can change your perspective on nature, encouraging you to pay attention to the world around you. Trees, to me, are like nature’s storytellers. They’re such prominent parts of the landscape, and a single tree can tell you a lot, not only about itself, but about the history and the present of an area. Its size can tell you when it was planted. The species can tell you what animals may be present, using the tree for survival. I have always considered it important to be in touch with my local environment. If I know all the plants and animals when I’m walking through a park, I feel like I’m walking with friends, even if I’m by myself.

I think when I started this class I was in the process of “curing” my tree blindness. I took Woody Plant ID a year ago, and I remember a good amount of information, but there’s also a good amount that I’ve forgotten, and an even greater amount I have yet to learn. I hope that this assignment will help me brush up on my tree ID and get me closer to curing my tree blindness! Our goal was to document eight native trees. I chose Glen Echo Park as my study site, so every tree on the list was located there. Continue reading to follow me on my journey of tree discovery!

Sugar Maple – Acer saccharum

My first tree is one that I immediately recognized, having taken several silviculture classes before this. Sugar maple is a common understory tree in many Ohio forests, with some even reaching the canopy. This particular juvenile was situated on the upper slopes of the ravine that makes up Glen Echo park. Maples are the only trees in the eastern US with opposite, fan-lobed leaves. Sugar maple can be distinguished from the other maples by its dark brown vertically ridged and scaly bark, and its usually five-lobed leaves with moderately deep notches between each lobe. If you couldn’t tell by the name, sugar maple is one of the most useful trees for maple syrup production.

Small Sugar Maple.

Canopy of Sugar Maple showing leaf detail.

Northern Red Oak – Quercus rubra

For my next tree, I came across a northern red oak. This one was another easy ID, its trunk laced with shiny strips of bark. The leaves are also a useful clue, with their bristle-tipped lobes. Northern red oak is (obviously) a member of the red oak group, whose acorns take two years to mature, unlike white oak acorns which take only a year. Red oak acorns are also higher in tannin content than white oak acorns, which means they taste far more bitter. So if you’re ever in a survival situation and you get the choice between white oak acorns and red oak acorns, maybe stick with the white oak.

Leaf detail of Northern Red Oak.

Bark detail of Northern Red Oak. Note the shiny smooth strips in between the coarser ridges.

Box Elder – Acer negundo

Also known as Ashleaf Maple, this mid-sized tree is unique for its opposite compound leaves, unlike other maples which have opposite simple leaves. The leaflets number 3-5 (sometimes 7) and may be coarsely toothed. The twigs are often a green color. This tree was right next to the creek at the bottom of the ravine, which is typical of this species as they enjoy damp soils. The common name comes from the soft white wood of the tree which is used to make boxes.

Leaf detail of Box Elder. Note the pinnately compound leaves, and the occasional coarse teeth on the leaflets. Also note the purplish-green twigs.

Foreground: a small Box Elder.

Tulip-tree – Liriodendron tulipifera

A tall, stately tree that I find distinctive, particularly for its leaves. The leaves are alternate simple, and fan-lobed (think maples), but the top lobe is flat, creating a squared-off shape. The bark is light gray and has many vertical grooves. The common name comes from the flower’s resemblance to true tulips.

Leaf detail of Tulip-tree.

Bark detail of Tulip-tree.

Silver Maple – Acer saccharinum

This juvenile tree was on a bank right above the creek. I recognized it by the leaves, which are more deeply notched than other maples in the area. The bark was knobbly and dark gray. There’s actually quite a few of these trees planted as ornamentals around my house near South Campus, apparently they became popular landscaping trees after World War II as a replacement for the diseased American elm due to their rapid growth.

Leaf detail of Silver Maple.

Small specimen of Silver Maple.

American Elm – Ulmus americana

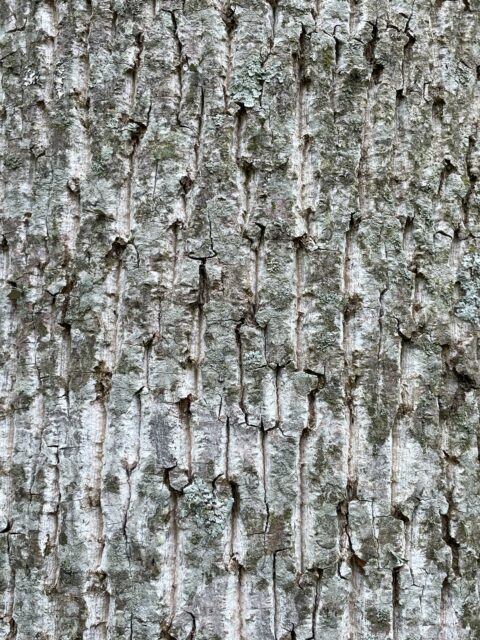

Speaking of American elm, I managed to find one near the large tunnel in the park. This species has unfortunately taken a hit to its population since the introduction of Dutch Elm Disease in the 1930s. The leaves are alternate simple, egg shaped, with toothed margins and a somewhat uneven base. The bark is more distinctive, it’s grayish and heavily grooved/textured. The fun part is that you can press it and it’s actually somewhat squishy! Peeling the bark will reveal white and brown colors beneath, which reminds me a bit of Neapolitan ice cream.

Bark detail of an American Elm. I peeled some of the bark to show the brown and white coloration underneath.

Leaf detail of American Elm. Note the uneven base.

Black Walnut – Juglans nigra

This tree looks almost tropical, with its lush foliage composed of alternate pinnately compound leaves. It often lacks a leaflet at the end of the leaf, distinguishing it from species with similar leaves. This tree was a juvenile, but was already beginning to display the unique dark, grooved bark. Black walnut has some of the most valuable wood in the timber industry and is in high demand for furniture.

Small specimen of Black Walnut.

Leaf detail of Black Walnut. Note many leaflets and absence of single leaflet at the end tip.

American Basswood – Tilia americana

Rounding out the list is this lovely specimen of American Basswood. I was immediately drawn by the foliage, the leaves are alternate simple, large and heart shaped, possess toothed margins, and have an uneven base like elms and hackberries. But this tree also had bracts present! These bracts are much different from the leaves, banana-shaped with smooth margins. The flowers of the Basswood will grow off the bracts, you can see in the images that they’re close to blooming. The bark is light gray with thin, shallow ridges.

Bract detail of an American Basswood tree. Note the flower stalk emerging from the top of the bract.

Bark detail of an American Basswood.

Leaf detail of an American Basswood.